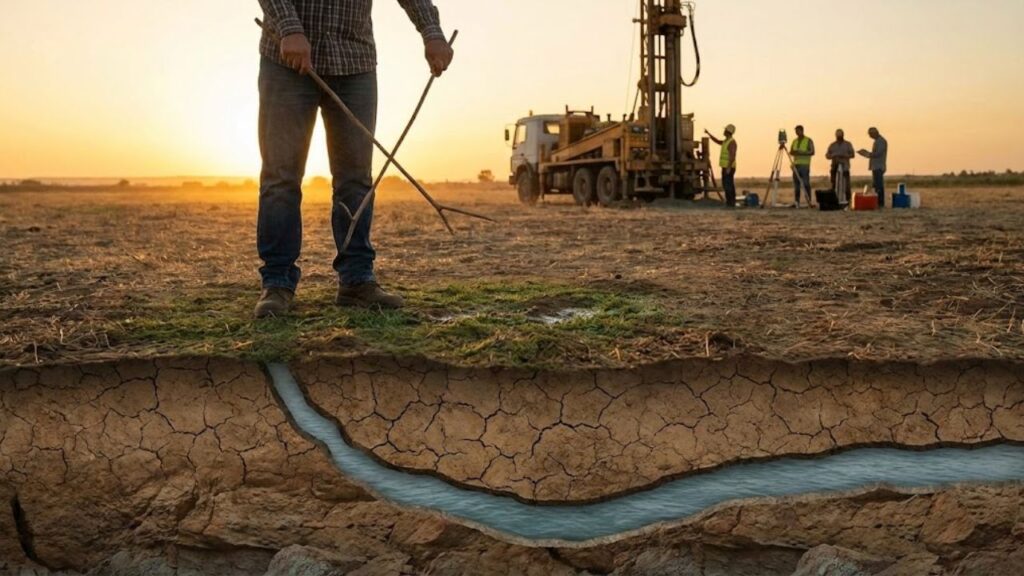

In Europe and North America, more homeowners are curious about tapping into underground water for purposes like lawn irrigation or even as a backup during water shortages. Before embarking on costly drilling projects, one big question remains: Is there a viable “water vein” beneath your property, or is it just dry, hard rock?

Reading the Land: How Water Moves Underground

The first step in groundwater exploration begins before any drilling takes place. Understanding how water moves beneath your land is crucial. Groundwater typically doesn’t form clear underground rivers. In most cases, it sits within layers of rock, sand, or gravel, where small pores and cracks store and channel the water.

Hydrogeological maps, which are made by public agencies or geological surveys, offer a great starting point. These maps show the types of rock present, identify known aquifers, and often indicate the typical depth at which water can be found in nearby boreholes. While these maps won’t tell you the exact location of water on your property, they will give you key insights:

- Is there an aquifer beneath your plot, or just dry rock?

- What depth have neighbors found water?

- Is the groundwater level stable or seasonal?

By consulting these maps, you can better determine whether a shallow hand-dug well is feasible or whether you’ll need to opt for deeper professional drilling.

Spotting Water Clues: What Vegetation and History Reveal

Your property and the stories shared by neighbors can offer valuable clues. Plants, especially, react quickly to the presence of moisture just a few meters below the surface. Look for signs like:

- Greener grass in summer along a strip compared to drier areas.

- Persistent damp patches in the soil, even after rain has stopped.

- Moisture-loving plants like reeds or rushes growing in certain parts of the garden.

- Taller crops along narrow bands in fields nearby.

These clues often suggest the presence of shallow groundwater or pathways where water flows more easily through the soil.

Additionally, local memories and old landmarks can point you toward water-rich areas. An abandoned well, a depression where a pond once stood, or the presence of trees like willows or poplars often indicate past access to groundwater.

Modern Tools for Groundwater Exploration: From Conductivity Surveys to Dowsing

Today’s groundwater prospecting uses advanced techniques like electrical conductivity surveys. Technicians use portable equipment to send weak electrical signals into the ground, which help identify wet or more permeable zones where water might be easier to extract.

While conductivity surveys aren’t inexpensive, they’re useful when:

- Your drilling budget is high and failure would be costly.

- The local geology is complex or poorly documented.

- Multiple wells are planned, such as on a farm or shared estate.

For a more hands-on, low-tech approach, digging a small trench or trial pit can provide direct insight into the soil’s moisture levels. A mini-excavator can help reveal whether water seeps in or if the ground remains dry. However, it’s essential to check for any underground utilities before proceeding.

Summary: Blending Old and New Methods for Groundwater Success

Finding groundwater is not just about drilling blindly. A combination of traditional methods like observing vegetation and local history, alongside modern techniques such as conductivity surveys, increases the likelihood of success. Whether you rely on hydrogeologists or even the help of a dowser, every piece of information can guide you toward the right spot, making your well more efficient and cost-effective.

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Aquifer | Layer of rock or sediment that stores and transmits groundwater in usable quantities. |

| Static Level | Height of water in a well when the pump is off and water is at rest. |

| Drawdown | Drop in water level inside the well while pumping. |

| Yield | Volume of water a well can supply per hour without damaging the aquifer. |