“Mysterious alien signal detected!”, avec une image violet flashy d’un vaisseau spatial sorti d’un vieux film. Pendant trois secondes, on se dit : *et si c’était vrai ?* Puis on retourne à nos mails, en se disant que ça doit être un bug, une exagération, un titre attrape-clic de plus.

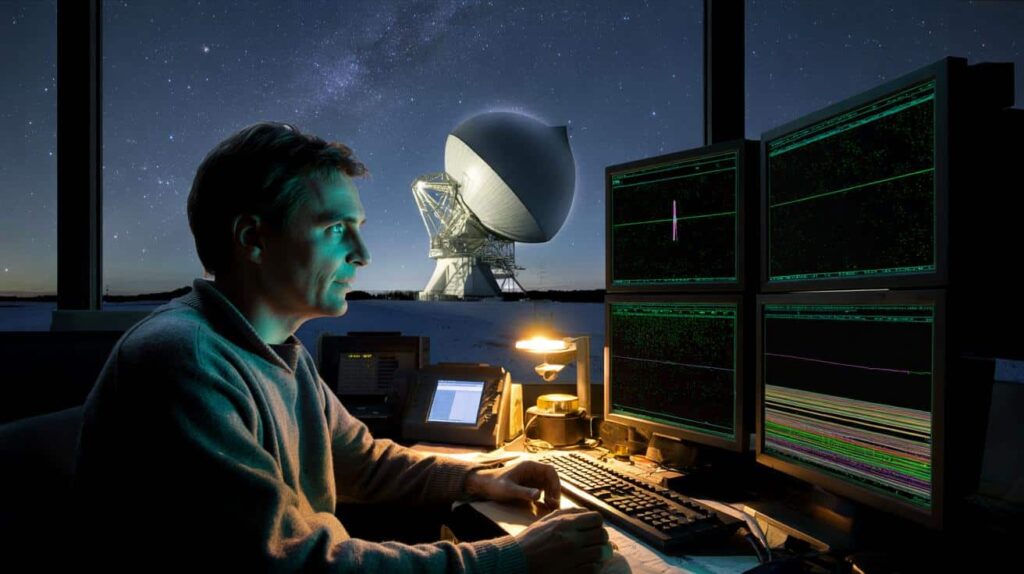

Un soir d’hiver à l’observatoire de Jodrell Bank, dans le nord de l’Angleterre, le dôme géant se détache sur le ciel noir. Il fait froid, le café est tiède, et un chercheur fixe un écran où défilent des courbes vertes et des chiffres qui n’intéresseraient personne sur TikTok. Pas de lumière verte, pas de message “We are here”, juste un bruit de fond obstiné, quasi ennuyeux.

Ce soir-là pourtant, au milieu du “brouhaha” cosmique, un signal très fin se détache, presque trop parfait. Et soudain, derrière l’écran, quelqu’un arrête de respirer une demi-seconde.

Why “strange radio signals” make headlines while astronomers chase the boring stuff

When a telescope catches a spike in radio waves from space, the story almost writes itself: mysterious, distant, maybe alien. Headlines love that kind of thing. “Strange radio signal from interstellar object” sounds like the prologue to a sci‑fi film, not a dry research paper with error bars and follow‑up checks.

The reality behind those stories is usually far less cinematic. Astronomers sit in dark rooms, surrounded by humming machines and old coffee cups, trying to work out whether the latest “whoa” moment is just a passing satellite, a mobile phone tower, or someone’s microwave. Most of the time, the climax of the story is a shrug and a technical note no one outside the field will ever read.

Yet that gap between the public excitement and the scientific routine is exactly where things get interesting. Because the truth is: the search for life in the cosmos is built on chasing what’s normal, not what’s flashy.

Take one of the most famous cases: “Wow!” signal, August 1977. A narrowband radio burst so striking that an astronomer circled it in red pen and wrote “Wow!” in the margin. No one has detected it again. No pattern. No repeat performance. Just one lonely spike in the noise.

Then there’s the more recent uproar around signals from interstellar visitors like ‘Oumuamua or comet Borisov. A slight anomaly in brightness, a weird trajectory, a whisper of radio noise, and suddenly your timeline fills with speculation about alien probes. Most scientists, reading the same data, quietly know the likely answer is mundane physics plus incomplete information.

Even the famous FRBs – fast radio bursts – started as “maybe aliens?” candidates. Now we know many are linked to extreme astrophysical objects like magnetars. They’re wild, yes, but they’re also natural. The pattern repeats: a dramatic headline, a sober re‑analysis, and the slow, careful shift from “mystery” to “catalogued phenomenon with a messy name.”

Here’s the awkward bit: science prefers repeatability, boredom, patterns. A single wild signal that never returns is more frustrating than thrilling. Real discovery, the kind that rewrites textbooks, tends to come from data sets so dull they’d never trend on social media. The kind of plots that look like someone dropped static on a spreadsheet.

So why do astronomers keep getting dragged into alien hype cycles? Partly because “we found another puzzling but probably natural radio source” doesn’t pay for observatories. Funding bodies and media outlets respond better to words like “extraordinary” than “low‑statistical significance anomaly.” The tension between storytelling and accuracy is baked into the way modern science is communicated.

Soyons honnêtes : personne ne lit vraiment chaque rapport technique sur ces signaux. People skim headlines, share a screenshot, and move on. In the lab, though, teams keep listening, day after day, patiently building the archive of “boring” that may, one day, make the extraordinary stand out for real.

How astronomers really listen for life in the noise

Strip away the clickbait, and the actual method is almost disappointingly methodical. First, you point a sensitive radio telescope at a region of sky: a sun‑like star, a patch rich in exoplanets, or sometimes just a blank field as a control. Then you record everything. Frequencies, intensities, time stamps. Hours and hours of what sounds, if you could hear it, like hissing static.

The clever bit comes later, in software and statistics. Researchers look for ultra‑narrowband signals, the kind nature doesn’t easily produce. They check whether a signal drifts in frequency in a way that matches a moving transmitter on a distant world, rather than a satellite zipping overhead. They compare on‑target and off‑target observations to see if the “signal” follows the telescope or the sky. The goal is simple: rule out Earth before you even whisper “alien”.

There’s a kind of humility baked into this approach. Astronomers know they live inside a planet wrapped in technology, spewing radio waves in every direction. So they build pipelines designed to doubt themselves first. That means cataloguing local interference, logging airplane routes, monitoring mobile networks, even tracking old observatory equipment that tends to misbehave when it rains.

History is full of cautionary tales. One of the most famous is the saga of the “perytons” at the Parkes radio telescope in Australia. For years, researchers picked up strange, short radio bursts that looked tantalisingly like cosmic signals. They arrived at odd times, didn’t quite fit known astrophysical sources, and haunted the data like ghosts.

After painstaking detective work, the culprit turned out to be… a microwave oven in the staff kitchen. When someone opened the door early to stop it, the microwave leaked a brief, distinctive burst of radio noise. It just happened to look cosmic if you didn’t know what you were dealing with. A perfect reminder that the universe sometimes shares a punchline with sitcoms.

On another occasion, the famous Breakthrough Listen project spotted a narrowband signal from the direction of Proxima Centauri, our nearest star neighbour. It made headlines as a “candidate technosignature”. Months of follow‑up work later, the team concluded it was almost certainly terrestrial interference. No secret code, no message in the noise, just human tech reflecting human hopes back at us.

This pattern is why astronomers flinch a little when a “strange signal” story goes viral. They’ve seen how it ends. Long nights of cross‑checking equipment logs, recalibrating antennas, replaying old data to find the glitch, then trying to explain to the public that solving a puzzle with a boring answer is still progress, not failure.

The logical framework behind all this is brutal but fair: extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. That means you don’t get to shout “ET!” because of one spike on one chart. You need repeat detections at the same frequency, from the same patch of sky, with different instruments. You need the signal to persist, to behave in a way that screams “technology” rather than “clever natural physics”.

There’s also the background problem: the universe is loud. Pulsars, quasars, flaring stars, magnetars, plasma clouds – all of them leak radio signals. Many can mimic aspects of what we’d expect from alien transmitters. The job, then, isn’t to find radio waves. It’s to find radio waves that defy every natural explanation we can throw at them.

So astronomers build layers of scepticism into their workflow. Independent teams try to reproduce findings. Data sets get reanalysed with fresh algorithms. Observations are repeated months or years later. It’s slow, sometimes thankless work. Yet quietly, in the background, it’s teaching us how the universe talks to itself – even if nobody is talking to us. Not yet, at least.

How to read the next “mysterious space signal” headline like a pro

If you’re tired of the hype rollercoaster, there’s a simple mental checklist anyone can use. First question: is the signal a one‑off, or has it been seen again? If the article doesn’t mention repeat detections, treat it like a first draft, not a revelation. Real breakthroughs usually survive follow‑up observations; flukes don’t.

Next, look for who’s talking. Does the story quote the research team themselves, or just anonymous “experts say”? When astronomers are cautiously excited, they use careful language: “candidate”, “signal of interest”, “requires confirmation”. If the headline screams aliens but the scientists don’t, trust the quieter voices.

Finally, check whether the story mentions how interference was ruled out. Any solid study will talk about control observations, checks against satellite databases, cross‑checks with other telescopes. If that part is vague or missing, you’re probably reading the sizzle, not the steak. Curiosity is healthy, but so is asking: what did they eliminate before jumping to the exciting part?

Many readers feel a bit torn. On one hand, they crave the thrill: maybe this time it’s real. On the other, they’re tired of feeling duped by over‑sold “discoveries” that vanish three weeks later. That emotional whiplash is real, and it’s not your fault. The way science is packaged for clicks often strips away all the doubt and nuance that researchers work so hard to preserve.

One helpful habit is to treat every space signal story as an invitation, not a verdict. Instead of thinking “We’ve found aliens!” or “This is nonsense!”, try “This is the first interesting hint in a long process.” You can enjoy the drama while keeping a little mental distance. You’re allowed to feel wonder and scepticism at the same time.

And if you’re into sharing these stories online, adding a simple line like “early result, needs confirmation” already makes you part of the solution. It sets expectations for your friends and followers. It’s a small gesture, but it nudges the conversation away from disappointment and towards curiosity – that quieter, more sustainable fuel that science actually runs on.

“The universe doesn’t owe us a dramatic signal,” one radio astronomer told me. “Our job is to listen so carefully that, if something is out there, we’ll recognise it not by how strange it is, but by how consistent it becomes.”

Behind the headlines, a few simple ideas keep surfacing:

- Repeatability beats shock value – one wild spike is less convincing than a dozen quiet, matching detections.

- ***Boring is where science lives*** – long stretches of “nothing to see here” are exactly what make real anomalies meaningful.

- Context changes everything – a signal that looks incredible alone often turns ordinary once you know the local interference map.

Once you see those rules at work, the news cycle feels different. Less like a rollercoaster, more like a long conversation between us and a universe that, so far, mostly answers with silence and static. Which, strangely, makes the listening feel even more intimate.

The quiet beauty of not knowing (yet)

There’s a strange comfort in realising that most “mysterious” radio signals turn out to be fridge doors, passing planes, or human tech bouncing off the atmosphere. It means we’re not easily fooled anymore. The bar for wonder has been raised, and that’s a good thing. Awe that survives scrutiny is stronger than the instant rush of a viral headline.

At the same time, the search goes on, almost stubbornly. Night after night, telescopes stare at distant stars that look, from here, like pinpricks with no story. Computers sift terabytes of static for patterns that might never come. On paper, it sounds monotonous; in practice, it feels like keeping a tiny light on in a vast, dark house, just in case someone out there is also awake.

The next big signal might arrive next year, or in a hundred years, or never. That uncertainty is part of the deal. What we can choose, right now, is how we react when the alerts flare up on our screens again. We can demand better questions, sharper details, fewer promises. We can share the mystery without selling it as proof.

Gardeners urged to act now for robins : the 3p kitchen staple you should put out this evening

Gardeners urged to act now for robins : the 3p kitchen staple you should put out this evening

And if one day a signal does repeat, line up, survive every test we throw at it, the story will likely begin in the least cinematic way possible: a tired researcher staring at a graph that looks almost identical to yesterday’s, spotting a tiny difference that refuses to go away. No glowing saucers. Just data, and a quiet intake of breath, and the realisation that the universe has finally answered with something other than noise.

| Point clé | Détail | Intérêt pour le lecteur |

|---|---|---|

| Strange signals are usually mundane | Most “mysteries” fade after checks for interference and natural sources | Helps avoid disappointment after sensational headlines |

| Scientists chase patterns, not one‑offs | Repeatable, consistent signals matter far more than single spikes | Gives a simple rule to judge future news stories |

| You can read space news like an insider | Asking about repeatability, interference checks, and cautious language | Makes you a savvier, more confident consumer of science media |

FAQ :

- Are any “strange radio signals” still unexplained?Yes, a few signals like the original Wow! signal remain unexplained, but “unexplained” doesn’t automatically mean “artificial” – it often just means “not enough data yet”.

- How would scientists know a signal was really from aliens?They’d look for repeatability, a clear pattern or modulation, and behaviour that rules out known natural sources and human interference across multiple telescopes.

- Do astronomers expect to find a technosignature soon?Most are cautiously hopeful but realistic: it could happen tomorrow or never. The search is framed as a long‑term, open‑ended project, not a countdown.

- Why do the media hype these signals so much?Because “maybe aliens” headlines attract clicks and attention. The underlying studies are usually far more careful and modest in their claims.

- Can I follow real, less hyped updates about these searches?Yes. Projects like SETI, Breakthrough Listen, and major observatories share detailed updates on their own websites and social channels, often with links to the original papers.