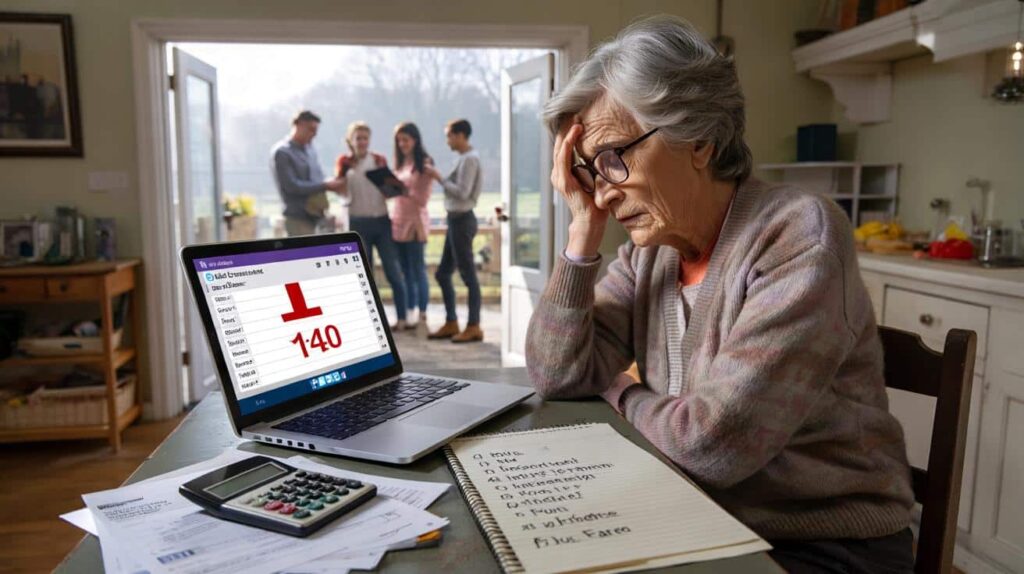

The email landed at 6:12 a.m., just as the kettle clicked off in a quiet kitchen in Sunderland. Margaret, 72, pulled her cardigan tighter, opened her laptop, and watched as the subject line snapped into focus: “Changes to your State Pension from February.” At first she thought it was a scam. The wording looked cold, almost robotic. Then she saw the number: minus £140 a month. Confirmed. Approved. No appeal link. No helpful helpline at the top in bold.

She sat down very slowly, the way you do when bad news arrives and your body suddenly feels heavier than your age. That £140 wasn’t “extra” to her. It was heating on for an extra hour in the evening, the nicer biscuits when the grandkids came round, the bus fares to her weekly choir.

On social media, hashtags were already trending. The anger was just waking up.

Pensioners lose £140 a month while perks pile up for the young

Across the UK, thousands of retirees are opening the same sort of message Margaret did. A short, oddly cheerful notification that from February their state pension will drop by roughly £140 a month. Not a delay, not a technical error, but a real cut that’s now been stamped, signed, approved. For people already living on thin margins, that number feels brutal, not abstract.

What’s making it sting even more is what they’re seeing at the same time. Rail discounts for younger workers. New tax-free savings incentives promoted to people in their 20s and 30s. TikTok videos sponsored by government campaigns trying to nudge “Gen Z investors” to save big. While one generation is being asked to “tighten their belts”, another is being handed gift vouchers for the future.

Take Brian and Sheila, both 69, from Swindon. Their monthly joint state pension is already mapped down to the last pound on a lined notepad they keep next to the phone. Rent. Gas. Electricity. Bus pass. Medication top-ups. They’d pencilled in an extra £30 for Sunday lunches with their grandchildren, a small ritual that made the week feel less grey. After the confirmed February cut, that line was the first to go.

“We’ll still see them,” Brian told me, staring at the notepad, “but it’ll be beans on toast now.” Around the country, charities estimate that this £140 reduction will hit tens of thousands of similar households. Age campaigners warn that even a £20 change can tip someone into fuel poverty. Here, we’re talking about the cost of an entire weekly supermarket shop evaporating, every single month.

*On paper, the government’s explanation sounds almost tidy.* Officials talk about “rebalancing resources” and “aligning benefits with long-term sustainability.” The message: there’s only so much money in the pot, and Britain’s ageing population is putting pressure on the system. Younger taxpayers are being courted with programmes to “reward work” and boost saving habits, from ISA tweaks to National Insurance breaks, while older citizens are told that “everyone has to play their part.”

Hidden inside that phrase is a quiet judgment: pensioners are a cost, younger workers are an investment. It’s a neat narrative for a press conference. Out in real kitchens, where kettles boil and emails arrive, the “rebalancing” looks a lot like choosing winners and losers.

How retirees are trying to cope – and what real people are actually doing

The first instinct for many retirees has been to go back to the basics and treat their budget like a serious project. People are digging out old bank statements, opening fresh spreadsheets, and listing every single direct debit from broadband to boiler cover. The goal is simple: find £140 a month before February bites. That might mean cancelling streaming services, renegotiating insurance, or swapping the car for a bus pass.

Some are moving money around in ways that feel quietly desperate. A small personal savings pot meant for emergencies gets dipped into “just to bridge the gap for a few months.” A credit card that used to live in the back of a drawer suddenly starts covering grocery runs. Let’s be honest: nobody really does this every single day, but a lot of older people are now reviewing their finances weekly, almost like a second job.

There’s also a more emotional type of cost-cutting you don’t see on spreadsheets. A widow in Kent told me she’s stopped switching the heating on in the afternoon “unless my hands actually hurt from the cold.” A former nurse in Glasgow has begun skipping her weekly pub quiz so she can put that £12 towards her energy bill. Little slices of joy, trimmed away to stop the red numbers creeping into their bank balance.

Many fear the slippery slope. One month you give up the nice coffee. Next month, you’re putting off dentist appointments. By spring, you’re wondering whether to ignore that strange noise the boiler is making. The cut doesn’t just shrink a budget, it shrinks a life. And when younger workers post videos celebrating new tax breaks or “government-backed saving hacks,” the contrast feels almost cruel.

The frustration has now moved from living rooms to pavements. Pensioners and their families have been writing to MPs, calling local radio stations and sharing screenshots of their pension letters online. The tone is rarely theatrical. It’s weary, edged with disbelief.

“After 45 years of paying in, I’m now told my share is being trimmed so that other people can be ‘incentivised’,” one retired bus driver from Birmingham wrote. “We’re not numbers. We’re the ones who kept the wheels turning when there were no remote jobs and no mental health days.”

Campaign groups are circulating simple, practical demands:

- Restore the £140 for the most vulnerable pensioners on low or no savings

- Publish clear, plain-English breakdowns of how age-based perks are allocated

- Give retirees at least 12 months’ warning before any future cuts

- Link minimum state pension levels to real-life living costs, not only inflation

- Create one helpline and website where older people can check every support they’re entitled to

The feeling is not just anger, but a plea to be seen.

A country arguing with itself about fairness and the future

When you step back from the furious headlines, what’s really unfolding here is a raw, uncomfortable national conversation about who gets looked after first. Younger taxpayers, already stretched by rent, student debt and eye-watering house prices, are being told they’re finally getting a bit of a break. Older citizens, who feel they “played by the rules” for decades, are suddenly being recast as a drag on the system just when they’re most fragile.

That tension runs through families too. Grandparents cutting back on gifts for birthdays so their children can keep paying nursery fees. Parents wondering if they’ll ever inherit anything now that their mum’s pension has been sliced. And somewhere in the middle, a generation in their 40s and 50s watching this fight unfold, knowing they may get the worst of both worlds: fewer perks now, a thinner pension later.

The £140 figure is technical on paper and visceral in practice. It’s food, heat, dignity, and a quiet sense that the state still has your back after a lifetime of tax and work. Whether this cut becomes a temporary political storm or a turning point in how Britain treats its older citizens depends on what happens next – in Parliament, yes, but also in how we talk about age, value and what we owe to one another.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Confirmed £140 cut | State pension reduced from February, impacting thousands of retirees on fixed incomes | Helps readers understand the scale and timing of the change hitting real households |

| Generational contrast | Younger taxpayers gain new perks and incentives while older people lose monthly income | Highlights the perceived unfairness driving anger and debate across age groups |

| Practical responses | Budget reviews, cutting non-essentials, contacting MPs, and using support organisations | Offers concrete ideas for those affected and their families to respond, not just panic |

FAQ:

- Question 1Is the £140 state pension cut really confirmed for February?

- Question 2Will every pensioner lose the same amount each month?

- Question 3Why are younger taxpayers getting government perks while pensions are reduced?

- Question 4What can I do if this cut pushes me into debt or fuel poverty?

- Question 5Could this decision be reversed if there’s enough public pressure?