On the edge of a fading Midwestern town, where the gas station closes at 7 and everyone still waves from their trucks, a widower thought he was doing something simple and good.

He had space. They had horses that nobody wanted. The kind with ribs showing, hooves cracked, and stories nobody really wanted to tell at the diner.

So he opened his gate and said yes.

On a cool Saturday, volunteers pulled in with borrowed trailers, kids carried buckets, and someone set a crockpot on a folding table. There was hay, water, soft voices, a few nervous laughs.

Above them, only the wide sky and the low hum of a town trying to stay alive.

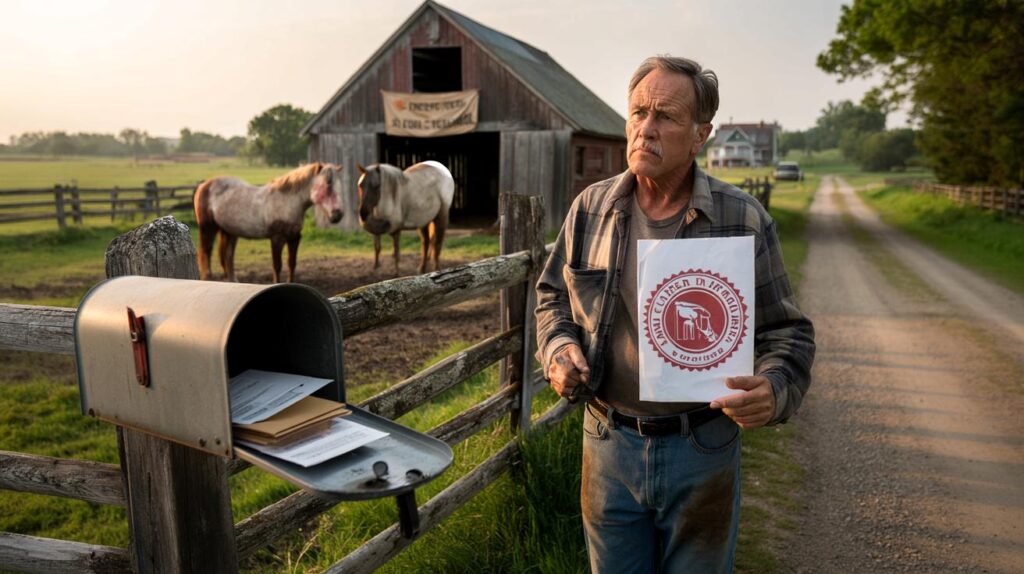

Two weeks later, he got a letter from the county.

$2,000 Direct Deposit for U.S. Citizens in February Eligibility, Payment Dates & IRS Instructions

$2,000 Direct Deposit for U.S. Citizens in February Eligibility, Payment Dates & IRS Instructions

The envelope said “Notice of Violation.”

The reason? “Agricultural activity” on residential land.

The day kindness met the zoning code

The widower’s name is Mark, 67, retired mechanic, the kind of man who still writes checks at the hardware store.

He lives at the end of a gravel road on two acres that used to be part of a farm, back when his wife planted tomatoes in coffee cans and left them on neighbors’ porches.

After she died, the house grew too quiet.

The TV stayed on a little longer, the coffee got colder on the counter.

When a small horse rescue group asked if they could temporarily use his pasture as a safe stop for seized animals, he felt something wake up again.

He told them, “My wife would’ve liked this.”

The rescue wasn’t some big operation with shiny trailers and matching jackets.

It was four women, two teenagers, and a Facebook page.

They worked with local animal control and nearby sheriffs, stepping in when neglected horses needed a place to land before heading to long-term foster homes.

That weekend, three emaciated mares and a shaggy old gelding arrived on Mark’s property.

Neighbors came by the fence.

Someone brought carrots.

A little girl from down the road stood on tiptoes to stroke a tangled mane.

By Sunday night, the horses had clean water, fresh hay, and a promise: they would never go back to where they came from.

For a brief moment, the whole place felt like it had purpose again.

Then came the complaint.

One nearby homeowner called the county to report “new livestock operation” and “increased agricultural activity.”

The zoning officer drove by, took photos from the road, and checked the map.

On paper, Mark’s parcel was zoned residential with no allowance for ongoing agricultural use.

No one cared that the horses weren’t being bred, sold, or used for profit.

The code didn’t distinguish between a commercial stable and a rescue stopover.

It just saw “horses = ag use.”

A week later, the fine landed: several hundred dollars, plus a warning that any repeat “violation” could trigger daily penalties.

That’s how a quiet man with a folding lawn chair and a borrowed muck rake ended up treated like an unlicensed feedlot.

When a good deed runs into a bad rulebook

The first thing Mark did was call the phone number on the notice.

He thought, maybe this is a mistake, maybe they just don’t know what we’re doing here.

The zoning clerk was polite, but firm.

Horses on residential land counted as agricultural land use under their local code.

Temporary or not, rescue or not, permission or not from animal control — the structure of the law didn’t bend for intent.

She suggested he apply for a special-use permit.

The fee: more than his monthly Social Security check.

The timeline: several months, public hearings, signage on his property, and no guarantee of approval.

He hung up the phone with his jaw tight and his kitchen clock suddenly too loud.

The rescue group felt blindsided.

They had paperwork showing their nonprofit status, email threads with an animal control officer, even thank-you comments from neighbors on social media.

But none of that erased the fact that the town’s zoning ordinance hadn’t really been updated since the ‘90s, when “rescue” sounded more like a word for TV dramas than grassroots animal welfare.

The internet had moved on.

Volunteer networks had exploded.

Communities had learned to crowdsource compassion.

The rulebook, though, stayed frozen in time.

So the group scrambled.

They relocated the horses earlier than planned to a rented pasture in the next county, paying out of pocket.

They launched a small fundraiser to help Mark with the fine and costs.

The comments flooded in: “How is this illegal?” “This is insane.” “A man helps animals and gets punished?”

Legally, the town wasn’t exactly “wrong.”

On a strict reading, many rural communities classify any ongoing horse presence as agricultural, even if there’s no money involved.

The theory is simple: horses bring traffic, noise, manure, and possible water runoff issues.

So they get lumped in with farms and large-scale operations, regardless of context.

But on the ground, it feels wildly out of step with real life.

More families keep backyard hens, foster goats, or host rescues for a few weeks.

Zoning codes that were written to prevent factory-style production end up kneecapping small-scale kindness.

Let’s be honest: nobody writing those ordinances imagined a widower quietly hosting starved horses for a handful of volunteers with donated hay.

The distance between the text of the law and the texture of lived reality has rarely felt so wide.

How people in small towns quietly push back

Across rural America, people have started to learn a new survival skill: reading their local zoning code like a recipe.

Not because they love legal language, but because one anonymous complaint can sink a good idea overnight.

The simplest move many rescues make now is to spread their activities across multiple properties.

One person holds short-term “quarantine,” another covers rehab, a third volunteers pasture for long-term fosters — often on land properly zoned for agriculture.

Others request written clarification before a single animal arrives, asking county staff to confirm, in email, what is and isn’t allowed.

It feels cautious, almost paranoid, but one saved email can stop a fine in its tracks.

There’s also a quiet, stubborn kind of organizing happening at the edges of places like Mark’s town.

People go to planning board meetings they’d rather skip, sign up for the messy early stages of zoning rewrites, and tell very human stories into stiff microphones.

This is where the emotional shock of a fine turns into slow, patient change.

Residents ask for clearer definitions: What’s the difference between agricultural production and rescue?

Between a commercial boarding stable and a temporary rehab station?

The most common mistake is assuming “everyone knows what I’m doing, so it’s fine.”

That might work for years, right up until the one neighbor who hates manure smells or extra traffic decides to call the county.

The rule is simple but brutal: if it isn’t written down, goodwill doesn’t count.

Some communities have begun to carve out room for common sense.

They add specific language for small-scale rescue work, cap the number of animals, or set time limits for stays instead of banning the activity outright.

One rural planner told me, *“We used to think in terms of crops and cows. Now we’re talking about fosters and nonprofits.”*

The shift is slow, but it’s happening.

In a nearby county, a board member pushed through a tiny but powerful change: a new category dubbed “compassionate use.”

It covers short-term care for seized, abandoned, or rescued animals on residential land, under clear conditions — no breeding, no sales, limited numbers, defined timeframes.

“That one phrase gave us a way to say yes, instead of just no,” she said.

- Check your zoning map before saying yes to hosting animals.

- Ask for written clarification on rescues, not just a friendly phone nod.

- Push for specific wording like “rescue,” “foster,” or “compassionate use” in local codes.

- Document cooperation with animal control or shelters.

- Tell your story publicly when a good deed collides with a bad rule.

A fine that turned into a question for the whole town

In the diner where Mark once fixed the jukebox for free, people now lower their voices when the horses come up.

Not out of shame — out of that complicated small-town mix of loyalty, anger, and tired hope.

The fine got mostly paid by strangers online.

The horses are safe, gaining weight in a different field.

Life, as it does, keeps rolling forward in pickup trucks and school buses.

But something lingers.

Who gets to decide what counts as “agriculture” when what’s really happening is mercy?

How many good deeds are we willing to cram into outdated boxes before we decide the boxes need to change?

For some, this is just a story about one man, a few horses, and an overzealous code.

For others, it’s a mirror held up to the way we write rules: clean on paper, messy on the ground.

We’ve all been there, that moment when a small, decent act suddenly feels bigger than you, tangled in systems you never wanted to learn about.

Sometimes a zoning violation is just that.

Sometimes it’s the nudge that forces a whole town to ask: what kind of place do we really want to be?

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Know your zoning | Residential land may treat horses as “ag use” even for rescue | Prevents surprise fines and painful conflicts |

| Get it in writing | Email confirmations from county staff can protect good-faith efforts | Gives leverage if policies shift or complaints appear |

| Push for change | Ask for clear categories like rescue or “compassionate use” in ordinances | Helps align local rules with modern, community-based animal care |

FAQ:

- Can I host a rescue animal on my property without breaking the law?Often yes, but it depends entirely on your local zoning code and how your land is classified, so always check before committing.

- Does a nonprofit status protect a rescue from zoning fines?No, zoning applies regardless of nonprofit status; the land use category matters more than the organization’s paperwork.

- Are horses always considered “agricultural” under the law?In many rural areas they are, even when kept as companions or rescues, though some places are starting to recognize different categories.

- What can I do if a neighbor complains about rescue animals?Stay calm, document your communication with authorities, and ask the county to clarify in writing what’s allowed and what needs to change.

- How can I help change outdated animal-related zoning rules?Show up at planning meetings, share local stories like Mark’s, and propose specific wording that protects small-scale, humane rescue work.