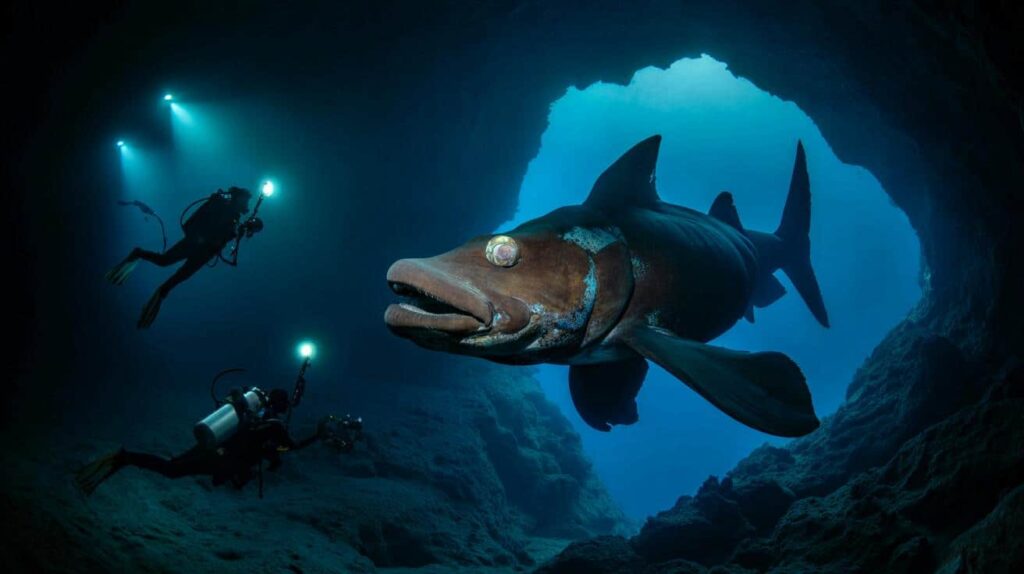

The first thing they saw was an eye. A round, glassy, unblinking eye, hanging in the blackness like a small, ancient moon. The French divers had been descending along the steep Indonesian reef wall for long minutes, their beams of light swallowed almost instantly by the abyss. The computers on their wrists ticked past 100 meters. Then 110. Then 120. The hum of their rebreathers and the distant crackle of the reef were the only sounds. And suddenly, out of the dark, that eye.

They all knew the shape from old black‑and‑white photos in biology books.

They also knew nobody had ever filmed it alive, in this place, at this depth.

A blue shadow from another time

At around 120 meters, the limestone wall gave way to a kind of ledge, a balcony suspended over the bottomless blue. The French team, a handful of highly trained technical divers and an Indonesian guide, moved slowly along this natural terrace. The water temperature dropped, their fingers numbed slightly inside thick gloves. Then a beam of light brushed against a strange silhouette. Not the quick dart of a tuna. Not the rigid armor of a grouper. Something slower. Almost hesitant.

A large body, mottled with flecks, blue and brown and ghostly, rotating on its axis in an odd spiral.

The divers froze. The cameras didn’t. One of them hit record with clumsy fingers, trying not to shout into his regulator. Before them, in the beam of three lamps, drifted a coelacanth, the legendary “living fossil” that scientists once thought had vanished with the dinosaurs. Its lobe-finned limbs paddled like four miniature legs. Its tail undulated with a quiet, prehistoric grace.

For long seconds, nobody moved. The fish turned its head, regarded the lights, then retreated slowly into a crack in the cliff, as if reversing into time itself.

The footage they brought back would become a first for this corner of Indonesia.

Long considered “corny,” this hairstyle is actually the one a hairstylist recommends most after 50

Long considered “corny,” this hairstyle is actually the one a hairstylist recommends most after 50

Behind the magic of the moment lies years of patient obsession. These divers didn’t just drop into the water and get lucky. They had cross‑checked old fishermen’s stories, scanned scientific papers, analyzed bathymetric maps to locate steep drops where the current cools. The coelacanth is a creature of twilight and shadow, usually hiding deep in caves during the day. To meet it, you have to play by its rules, descend into its night.

What looked like a miracle on the surface was, underwater, a calculated dance with depth, risk, and a species that has barely changed in 400 million years.

How you “meet” a living fossil without ever touching it

To capture these images, the French team had a very simple ritual: slow everything down. They didn’t rush their descent, didn’t chase every suspicious shape in the dark. Once they reached the target depth, they switched to a kind of underwater “silent mode”: no big fin kicks, no sudden flashes, no angry clouds of silt.

The coelacanth is shy, half-blind, and deeply sensitive to light changes. So they narrowed their beams, dimmed them, and swept them methodically along the rock wall, like careful hands turning pages in a book that might fall apart.

Many divers dream of extreme depths and rare animals, then end up with nothing but pretty bubbles on their GoPro. We’ve all been there, that moment when you realize you spent the whole dive chasing instead of observing. The French team did the opposite. They prepared for months on land, rehearsing emergency drills, testing lights, stabilizing their camera rigs so they could film with almost no body movement.

Let’s be honest: nobody really does this every single day.

Yet this is what separates a random encounter from a documented first — the kind of footage that scientists and conservationists actually use.

At one point during the expedition, a diver later confessed he almost broke the rule. The first time a large shadow passed in the distance, his finger twitched toward the high‑power setting on his torch. He wanted to flood the scene with light, to “get the shot.” Instead, he remembered the plan. Keep it soft. Keep it narrow. Accept the grain, accept the mystery.

The coelacanth is not a trophy, he told me. It’s a neighbor from another era. You don’t blind a neighbor in their own living room just because you’re excited.

- Soft, focused lights: lower intensity, narrow beams, no sudden bursts.

- Neutral buoyancy: stabilizing the body so the camera, not the fins, does the moving.

- Quiet contact: no touching, no herding, no cornering the animal for a “better angle.”

- Exit strategy: clear time limits at depth, whatever happens, even if the dream fish appears late.

Why these blurry blue images change the way we look at the ocean

The French divers didn’t bring back glossy, National Geographic‑style close‑ups. They returned with trembling, slightly grainy footage of a large blue fish turning in a shaft of light, far, far from the surface. On social networks, some commenters complained: too dark, too fuzzy, not epic enough. Yet something else happened. Indonesian researchers, who knew coelacanths from museum jars and sonar echoes, watched those same blurry seconds on repeat.

For them, the value wasn’t aesthetics. It was proof. Location. Behavior. Depth. Time of day.

Those coordinates, shared with local science teams, open the door to serious protection measures. A living coelacanth population means fragile habitats: deep caves, cold upwellings, a food chain that still works. When such a species disappears, it doesn’t just “go away.” It often signals a chain reaction, a quiet collapse that only becomes visible years later at the surface — fewer fish in markets, bleached reefs, villages losing their livelihoods.

*Seeing one coelacanth alive is like reading a very old text that somehow survived a fire.*

There’s also the emotional shock. Meeting a creature that swam before trees covered the continents can flip the way you see your own daily timeline. The divers admit it: after the expedition, routine emails and traffic jams felt strangely… small. That’s the plain truth of these “living fossil” stories: they remind us that our sense of urgency is very recent, very human, and often very short‑term.

**The coelacanth doesn’t rush. The ocean doesn’t rush. We’re the impatient ones.**

And once you’ve watched a 400‑million‑year‑old neighbor disappearing back into the dark, your idea of what deserves protection tends to expand, quietly but permanently.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Deep preparation pays off | Months of planning, training, and gear testing led to a few precious seconds of footage | Shows that rare “miracles” often come from patient, invisible work |

| Respectful observation | Low‑impact lighting, no contact, strict time limits at depth | Helps understand how to interact ethically with wildlife, even as a tourist or amateur diver |

| Scientific ripple effect | Location and behavior data shared with Indonesian researchers | Connects a viral story to concrete conservation outcomes in real places |

FAQ:

- Why is the coelacanth called a “living fossil”?Because its body plan has barely changed for hundreds of millions of years and it closely resembles fossil specimens from the dinosaur era, even though it’s very much alive today.

- Is this the first time a coelacanth has been filmed?No, coelacanths have been filmed before in places like South Africa and the Comoros, but this French team captured the first documented images in this specific Indonesian deep‑reef zone.

- How deep do coelacanths live?They usually rest between 100 and 200 meters, in dark caves or along steep drop‑offs, rising slightly in the water column at night to feed.

- Can recreational divers see a coelacanth?Almost certainly not: the depths involved require advanced technical training, special equipment, and very strict safety protocols that go far beyond standard recreational diving.

- Why does this discovery matter for non‑divers?Because it proves that some ancient, fragile ecosystems are still functioning, and that decisions made on land — from fishing policies to climate choices — will decide if these quiet neighbors from another age survive our century.