Rather than exposing the entire body to toxic drug cocktails or high-energy radiation, scientists are exploring a light-activated method that heats only cancer cells. The goal is simple but powerful: damage malignant tissue while leaving healthy cells largely untouched. Early laboratory tests suggest this approach could dramatically reduce the collateral damage long associated with traditional cancer care.

Why conventional treatments come at a cost

For decades, cancer therapy has relied on force over precision. Chemotherapy drugs circulate through the bloodstream to attack fast-growing cells, while radiotherapy beams deliver concentrated energy to tumours. Surgery removes suspicious tissue outright. These methods save lives, but they often leave patients dealing with lasting side effects such as nausea, exhaustion, hair loss, nerve pain, or organ damage. Many people accept this burden as unavoidable, even when the toll lingers long after treatment ends.

Researchers aiming for accuracy, not aggression

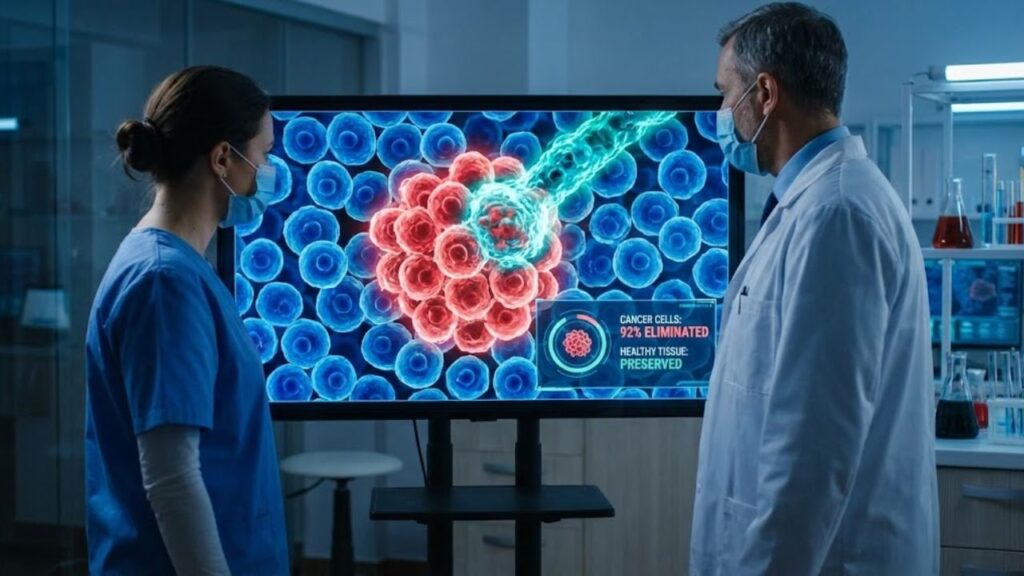

A collaborative team from the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Porto is working to change that balance. Their findings, published in ACS Nano, describe a technique designed to strike tumour cells with near-surgical accuracy. In laboratory conditions, the experimental method destroyed up to 92% of targeted cancer cells while sparing surrounding healthy tissue, hinting at a future where treatment does not turn the whole body into a battlefield.

How light and tin combine to kill cancer cells

The approach relies on photothermal therapy, a process where light is converted into heat. Scientists introduce specialised materials near a tumour and then apply a specific light wavelength. In this case, the material consists of tin oxide nanoflakes, known as SnOx, each only a few billionths of a metre wide. When exposed to near-infrared light, these particles heat up efficiently, creating a local temperature spike that cancer cells struggle to survive.

With its 337 metres and 100,000 tonnes, the largest aircraft carrier in the world rules the oceans

With its 337 metres and 100,000 tonnes, the largest aircraft carrier in the world rules the oceans

Tiny particles with powerful effects

The SnOx nanoflakes act like microscopic heaters. Researchers place them close to cancer cells and illuminate the area using near-infrared LEDs. The particles absorb the light and release heat only in their immediate surroundings. This highly localised warming damages malignant cells while leaving neighbouring healthy tissue mostly unharmed. Importantly, the system uses low-cost LED light rather than complex medical lasers, lowering both expense and technical barriers.

What laboratory tests reveal so far

In controlled cell-culture experiments, the team tested multiple cancer types. For skin cancer cells, a 30-minute LED exposure combined with SnOx nanoflakes eliminated up to 92% of malignant cells. Nearby healthy cells showed minimal harm. Colon cancer cells proved tougher, with roughly half destroyed under identical conditions. This difference underscores a key reality: cancer diversity means no single strategy works equally well for all tumours.

Consistency across repeated treatments

Beyond raw effectiveness, the researchers also examined durability. The tin-based particles remained thermally stable through repeated heating cycles, an important factor if treatments must be applied multiple times. While the results come from lab dishes rather than living patients, scientists see them as a strong proof of concept that justifies further development and testing.

Why choosing LEDs is a turning point

Many earlier photothermal experiments relied on medical-grade lasers. While precise, lasers are expensive, difficult to maintain, and risky if misused. The Texas–Porto team opted instead for near-infrared LEDs, a mature technology already common in electronics and simple medical tools. LEDs are cheaper to produce, easier to control, and deliver gentler light, reducing the risk of unintended tissue damage.

Advantages of LED-based therapy

- Lower manufacturing costs compared with lasers

- Compact, portable devices suitable for clinics or bedside use

- Reduced burn risk due to diffuse light delivery

- Simpler integration into patches or handheld tools

From operating room to portable care

One of the most striking ideas emerging from the research is portability. Physicist Artur Pinto and colleagues in Portugal have described compact LED devices that could be applied to the skin after surgery. Imagine a patient whose tumour has been removed, but residual cancer cells remain. A flexible LED patch, paired with tin nanoflakes placed in the surgical area, could deliver repeated gentle heating sessions to eliminate lingering cells and lower the risk of relapse.

A complementary tool, not a replacement

Researchers stress that this method would not immediately replace surgery or chemotherapy. Instead, it could serve as a supportive therapy, reducing recurrence risk without adding systemic toxicity. Wearable LED patches might deliver sessions lasting less than an hour, offering a less disruptive option alongside existing treatments.

Which cancers may benefit most

The technique appears best suited to tumours that are close to the body’s surface, accessible via endoscopic tools, or localised rather than widespread. Near-infrared light penetrates only a few centimetres into tissue, limiting its reach for deep or diffuse cancers. With support from the UT Austin Portugal programme, the team is now exploring applications in breast cancer and other tumours reachable with light-emitting probes.

Safety questions still to be answered

Any treatment involving nanomaterials raises important concerns. While tin oxide is widely used industrially, scientists must confirm how these particles behave inside the body over time. Key questions include particle accumulation, potential immune reactions, and interactions with other treatments. Regulators will require clear data before approving human trials.

Key risks and unknowns

- Heat control: keeping damage confined to tumour cells

- Treatment frequency: matching existing cure rates

- Patient operation: safe use outside hospitals

- Therapy interactions: compatibility with drugs and implants

How this fits into modern cancer care

This light-driven approach aligns with a broader shift toward precision oncology. Immunotherapies, targeted drugs, and gene-based tools all aim to attack cancer more selectively. Photothermal treatments could complement these methods, for example by weakening tumours before immune-based therapies or reducing the total chemotherapy dose needed.

Understanding the science behind the headlines

Several core concepts underpin this research. Near-infrared light penetrates tissue more deeply than visible light without damaging DNA. Nanoflakes, shaped like thin plates, absorb and release heat efficiently. The photothermal effect converts light energy into heat at specific wavelengths. As this technology advances, patients may encounter these terms during consultations, making basic understanding increasingly valuable.

A glimpse of a gentler future

For now, the evidence comes from laboratory studies, not patients. Still, the idea that a simple LED light and engineered tin particles could quietly destroy cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue offers a hopeful vision. It suggests a future where precision and gentleness matter as much as raw power in the fight against cancer.